Computing the permanent

In mathematics, the computation of the permanent of a matrix is a problem that is believed to be more complex than the computation of the determinant of a matrix despite the apparent similarity of the definitions.

The permanent is defined similarly to the determinant, as a sum of products of sets of matrix entries that lie in distinct rows and columns. However, where the determinant assigns a ±1 sign to each of these products, the permanent does not.

While the determinant can be computed in polynomial time by Gaussian elimination, Gaussian elimination cannot be used to compute the permanent. In computational complexity theory, a theorem of Valiant states that computing permanents, even of matrices in which all entries are 0 or 1, is #P-complete Valiant (1979) putting the computation of the permanent in a class of problems believed to be even more difficult to compute than NP. It is known that computing the permanent is impossible for logspace-uniform ACC0 circuits (Allender & Gore 1994).

Despite, or perhaps because of, its computational difficulty, there has been much research on exponential-time exact algorithms and polynomial time approximation algorithms for the permanent, both for the case of the 0-1 matrices arising in the graph matching problems and more generally.

Contents |

Definition and naive algorithm

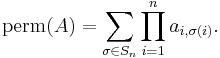

The permanent of an n-by-n matrix A = (ai,j) is defined as

The sum here extends over all elements σ of the symmetric group Sn, i.e. over all permutations of the numbers 1, 2, ..., n. This formula differs from the corresponding formula for the determinant only in that, in the determinant, each product is multiplied by the sign of the permutation σ while in this formula each product is unsigned. The formula may be directly translated into an algorithm that naively expands the formula, summing over all permutations and within the sum multiplying out each matrix entry. This requires n! n arithmetic operations.

Ryser formula

The fastest known [1] general exact algorithm is due to Herbert John Ryser (Ryser (1963)). Ryser’s method is based on an inclusion–exclusion formula that can be given[2] as follows: Let  be obtained from A by deleting k columns, let

be obtained from A by deleting k columns, let  be the product of the row-sums of

be the product of the row-sums of  , and let

, and let  be the sum of the values of

be the sum of the values of  over all possible

over all possible  . Then

. Then

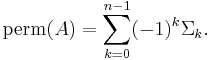

It may be rewritten in terms of the matrix entries as follows[3]

Ryser’s formula can be evaluated using  arithmetic operations, or

arithmetic operations, or  by processing the sets

by processing the sets  in Gray code order.

in Gray code order.

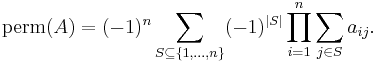

Glynn formula

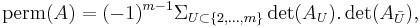

Another formula that appears to be as fast as Ryser's is closely related to the polarization identity for a symmetric tensor Glynn (2010).

It has the formula (when the characteristic of the field is not two)

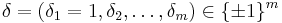

where the outer sum is over all  vectors

vectors  .

.

Special cases

Planar and K3,3-free

The number of perfect matchings in a bipartite graph is counted by the permanent of the graph's biadjacency matrix, and the permanent of any 0-1 matrix can be interpreted in this way as the number of perfect matchings in a graph. For planar graphs (regardless of bipartiteness), the FKT algorithm computes the number of perfect matchings in polynomial time by changing the signs of a carefully chosen subset of the entries in the Tutte matrix of the graph, so that the Pfaffian of the resulting skew-symmetric matrix (the square root of its determinant) is the number of perfect matchings. This technique can be generalized to graphs that contain no subgraph homeomorphic to the complete bipartite graph K3,3.[4]

George Pólya had asked the question[5] of when it is possible to change the signs of some of the entries of a 01 matrix A so that the determinant of the new matrix is the permanent of A. Not all 01 matrices are "convertible" in this manner; in fact it is known (Marcus & Minc (1961)) that there is no linear map  such that

such that  for all

for all  matrices

matrices  . The characterization of "convertible" matrices was given by Little (1975) who showed that such matrices are precisely those that are the biadjacency matrix of bipartite graphs that have a Pfaffian orientation: an orientation of the edges such that for every even cycle

. The characterization of "convertible" matrices was given by Little (1975) who showed that such matrices are precisely those that are the biadjacency matrix of bipartite graphs that have a Pfaffian orientation: an orientation of the edges such that for every even cycle  for which

for which  has a perfect matching, there are an odd number of edges directed along C (and thus an odd number with the opposite orientation). It was also shown that these graphs are exactly those that do not contain a subgraph homeomorphic to

has a perfect matching, there are an odd number of edges directed along C (and thus an odd number with the opposite orientation). It was also shown that these graphs are exactly those that do not contain a subgraph homeomorphic to  , as above.

, as above.

Computation modulo a number

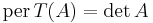

Modulo 2, the permanent is the same as the determinant, as  It can also be computed modulo

It can also be computed modulo  in time

in time  for

for  . However, it is UP-hard to compute the permanent modulo any number that is not a power of 2. Valiant (1979)

. However, it is UP-hard to compute the permanent modulo any number that is not a power of 2. Valiant (1979)

There are various formulae given by Glynn (2010) for the computation modulo a prime  . Firstly there is one using symbolic calculations with partial derivatives.

. Firstly there is one using symbolic calculations with partial derivatives.

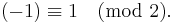

Secondly for  there is the following formula using the determinants of the principal submatrices of the matrix:

there is the following formula using the determinants of the principal submatrices of the matrix:

where  is the principal submatrix of

is the principal submatrix of  induced by the rows and columns of

induced by the rows and columns of  indexed by

indexed by  , and

, and  is the complement of

is the complement of  in

in

Approximate computation

When the entries of A are nonnegative, the permanent can be computed approximately in probabilistic polynomial time, up to an error of εM, where M is the value of the permanent and ε > 0 is arbitrary. In other words, there exists a fully polynomial-time randomized approximation scheme (FPRAS) (Jerrum, Vigoda & Sinclair (2001)).

The most difficult step in the computation is the construction of an algorithm to sample almost uniformly from the set of all perfect matchings in a given bipartite graph: in other words, a fully polynomial almost uniform sampler (FPAUS). This can be done using a Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithm that uses a Metropolis rule to define and run a Markov chain whose distribution is close to uniform, and whose mixing time is polynomial.

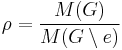

It is possible to approximately count the number of perfect matchings in a graph via the self-reducibility of the permanent, by using the FPAUS in combination with a well-known reduction from sampling to counting due to Jerrum, Valiant & Vazirani (1986). Let  denote the number of perfect matchings in

denote the number of perfect matchings in  . Roughly, for any particular edge

. Roughly, for any particular edge  in

in  , by sampling many matchings in

, by sampling many matchings in  and counting how many of them are matchings in

and counting how many of them are matchings in  , one can obtain an estimate of the ratio

, one can obtain an estimate of the ratio  . The number

. The number  is then

is then  , where

, where  can be approximated by applying the same method recursively.

can be approximated by applying the same method recursively.

Notes

References

- Allender, Eric; Gore, Vivec (1994), "A uniform circuit lower bound for the permanent", SIAM J. Comput. 23 (5): 1026–1049

- David G. Glynn (2010), "The permanent of a square matrix", European Journal of Combinatorics 31 (7): 1887–1891, doi:10.1016/j.ejc.2010.01.010

- Jerrum, M.; Sinclair, A.; Vigoda, E. (2001), "A polynomial-time approximation algorithm for the permanent of a matrix with non-negative entries", Proc. 33rd Symposium on Theory of Computing, pp. 712–721, doi:10.1145/380752.380877, ECCC TR00-079

- Mark Jerrum; Leslie Valiant; Vijay Vazirani (1986), "Random generation of combinatorial structures from a uniform distribution", Theoretical Computer Science 43: 169–188, doi:10.1016/0304-3975(86)90174-X

- van Lint, Jacobus Hendricus; Wilson, Richard Michale (2001), A Course in Combinatorics, ISBN 0521006015

- Little, C. H. C. (1974), "An extension of Kasteleyn's method of enumerating the 1-factors of planar graphs", in Holton, D., Proc. 2nd Australian Conf. Combinatorial Mathematics, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, 403, Springer-Verlag, pp. 63–72

- Little, C. H. C. (1975), "A characterization of convertible (0, 1)-matrices", J. Combin. Theory Series B 18 (3): 187–208, doi:10.1016/0095-8956(75)90048-9, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6WHT-4D7K7HW-H5/2/caa9448ac7c4e895fd7845515c7a68d1

- Marcus, M.; Minc, H. (1961), "On the relation between the determinant and the permanent", Illinois J. Math. 5: 376–381

- Pólya, G. (1913), "Aufgabe 424", Arch. Math. Phys. 20 (3): 27

- Reich, Simeon (1971), "Another solution of an old problem of pólya", American Mathematical Monthly 78 (6): 649–650, doi:10.2307/2316574, JSTOR 2316574

- Rempała, Grzegorz A.; Wesolowski, Jacek (2008), Symmetric Functionals on Random Matrices and Random Matchings Problems, pp. 4, ISBN 0387751459

- Ryser, H. J. (1963), Combinatorial Mathematics, The Carus mathematical monographs, The Mathematical Association of America

- Vazirani, Vijay V. (1988), "NC algorithms for computing the number of perfect matchings in K3,3-free graphs and related problems", Proc. 1st Scandinavian Workshop on Algorithm Theory (SWAT '88), Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 318, Springer-Verlag, pp. 233–242, doi:10.1007/3-540-19487-8_27

- Leslie G. Valiant (1979), "The Complexity of Computing the Permanent", Theoretical Computer Science (Elsevier) 8 (2): 189–201, doi:10.1016/0304-3975(79)90044-6

- "Permanent", CRC Concise Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2002

![\operatorname{perm}(A) = \left[\sum_\delta \left(\prod_{k=1}^m \delta_k\right) \prod_{j=1}^m \sum_{i=1}^m \delta_i a_{ij}\right] / 2^{m-1},](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/9f2ed0d9f0f4bac92bbdcee73b724939.png)